Another pebble in your shoe

Wednesday | December 13, 2006 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

“Life is a Dogme film. It’s hard to hear, but the words are still important.” This is one of the many in-jokes peppering Lars von Trier’s The Boss of It All, his newest feature. I watched it while preparing an essay for the Danish Film Institute, which superbly promotes Danish cinema to the world. But I wasn’t ready for what I saw.

It’s a comedy, of course, with a classic bait-and-switch premise. For shadowy motives, a corporate lawyer entices an idle actor to pretend to be the superboss whom the IT staff has never met. Unfortunately, through emails to the staff, the lawyer has constructed a persona for the boss–in fact, several personae, a different one for every worker. Our actor must play many parts before finally, in a series of reversals, he gets to “find” the real character.

In tone, the film is as mixed as most von Trier works, hovering between sympathy for idealistic underdogs and a sour realization that they will always be victims. It reminded me somewhat of Kaurismaki and the Fassbinder of Fox and His Friends. But the film is a breezy piece of work; nothing really serious faces his innocent here. There’s a lively satire of the corporate world, mocking management catchphrases du jour (not outsourcing, we’re told, but offshoring) and touchy-feely hugging. The hostile incomprehension between Denmark and Iceland provides some good gags too. Von Trier also pokes fun at actors, perhaps invoking his well-publicized feuding with divas like Kidman and Björk. Our hero/loser Kristoffer is a sort of Method man, but he learns that he gets the best results through shameless sentiment.

Here the words are important–it’s a very talky movie–but so are the pictures. Shot in 16mm in available light, The Boss breaks with von Trier’s normal commitment to handheld camerawork. Except for some interpolated crane shots outside the office building, the camera never moves, not even panning. But the image is constantly being refreshed through incessant cutting (there are over 1500 shots). The film boasts more jump cuts than Breathless or Matchstick Men, and each one creates a bump. There’s very little sound overlap between shots–the ambient noise usually drops out for a fraction of a second–and there are often visual mismatches, so (as in The Idiots), nearly every cut feels like an ellipsis. A film, von Trier has said, should be as irritating as a pebble in your shoe, and his abrasive tempo gives his comedy an anxious edge.

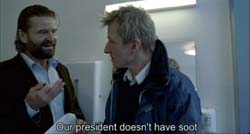

Then there are the very peculiar framings. Here’s a string of three brief shots from the first scene, with continuous dialogue (in gappy duration). The lawyer is trying to persuade the actor to perform as the boss.

(Yes, these are three separate shots, not three stages of one wobbly shot.)

These cuts break the so-called 30-degree rule, which mandates that if you’re cutting to different angles on the same subject, your second angle should vary by at least 30 degrees from the first. In addition, the later off-center compositions seem gratuitous; why not just sustain the first shot, since the next two hardly vary from it? Sometimes you get results like this.

It turns out that there is method to the madness, although the method, granted, is a bit mad. You can read about Automavision here, if you want to know in advance why the movie looks this way. But if you want to be as startled as I was, refrain. Let’s just say that von Trier’s famous 100-camera technique of Dancer in the Dark has been repurposed in a pretty unexpected way. And don’t believe what he says about surrendering to chance; the cuts are often very careful.

Whether you do your homework in advance or not, you’ll probably enjoy The Boss of It All. After my criticisms of editing in The Departed (which made me seem to be raining on the Scorsese parade) and my comments about classical principles of coverage, I’m happy to report on a film which offers something new and strange. The vivacious Danish film culture makes a space for von Trier to set up creative obstructions, for both himself and his viewers.

Postscript: Since I wrote this, von Trier announced that he’s added more tricks to his bag. Turns out that The Boss of It All employs Lookey, a game that challenges the viewers to spot objects that don’t belong in a scene. “For the casual observer it’s just a glitch or mistake,” he says, “but for the initiated it’s a riddle to be solved.” The purpose is to keep viewers alert and active. Film’s great flaw, he claims, is that “it’s a one-way medium with a passive audience.” Lookey, however whimsical, fits well with the agitating effects of the cut and sound dropouts.

The first viewer in Denmark to identify all the Lookeys correctly wins a cash prize and a chance to be an extra in von Trier’s next film.

PPS: Thanks to Vicki Synott of the Danish Film Institute.

PPPS 28 December: I just discovered a frisky website devoted to Nordic filmmaking, where Mirja Julia Minjares has gathered some interesting quotes from von Trier and his sound recordist Ad Stoop. Von Trier says that the computer program also selects for sound gain and filter. Adds Stoop: “When a computer program chooses the settings for the sound and cinematography between each shot, every edit gets underlined in the finished film.”

PPPS 31 December: Check perceptual psychologist Tim Smith’s blog for more insights into von Trier’s games with continuity editing.

–dB